|

William Benitz | Page last modified: |

|

William Benitz | Page last modified: |

Fort Ross: Because of its historical significance as a Russian settlement in the early 19th century, it is today a California state historical park. Its history is described in great detail on the Fort Ross Conservancy and California Parks web sites, as well as on Wikipedia (it omits the ranch era: 1842-1902). If you are unfamiliar with California’s early history, we recommend Wikipedia’s: History of California before 1900.

Very briefly...

For nine thousand years, the Kashaya band of the Pomo people lived undisturbed, relatively isolated on the Pacific coast. Their lands extended inland about 30 miles (50 km) between the Gualala and Russian river mouths. Hunter-gatherers, the band of about 1,500 members migrated to the coast in spring and summer to hunt and fish, returning inland to the warmer fog-free valleys in autumn and winter. The Kashaya knew (& still know) the vicinity of present day Fort Ross as Metini, where they had a village with an assembly house for ceremonial and social events. (From old photos, the village was up-hill the north-east of the fort.)

Although today the Kashaya are contemporary California Indians in a modern and fast-moving world, they still retain their strong feelings of attachment to their ancestral land and the way of life that was so long enjoyed by their ancestors. — Fort Ross Conservancy

Spain claimed northern California in 1592, though it did not establish settlements (presidios) and missions until the late 1700s — in reaction to possible British and Russian incursions from the north. But when in 1811 the Russians began settling along California’s northern coast, local Spanish officials lacked the resources with which to evict them. An unofficial agreement was reached on October 26, 1816, between the Spanish governor and the local Russian leaders: Spain retained title to the land, but the Russians would farm and graze it – until ordered to leave by their own superiors. Mexico regained full control when the Russians departed on January 1, 1842.

The Russians, in the form of the Russian-American Company, established a settlement at Metini: the Rossiia or Ross colony, settlement, or fortress. At its largest, during the 1830s, the settlement consisted of as many as 100 Russians (administrators & laborers) and 125 Alaskan Aleuts (hunters), augmented by Kashaya (laborers). The coastal mountains made it difficult to reach overland, thereby shielding it from harassment by the Spanish, & later Mexican, authorities.

The primary purposes of the settlement were to supply the fur trade with sea-otter pelts and the Russian colony in Alaska with food from crops and livestock. The Russians generally treated the Kashaya well and their relationship was predominantly friendly. Lacking women, some Russians and Aleuts took Kashaya wives; their children eventually comprised one-third of the colony’s population.

In 1841, after being there almost 30 years, the Russians abandoned Fort Ross; they had depleted the otter population, and better sources of food had been found for the Russian colony in Alaska. After offering it for sale first to the British (Hudson Bay Co.), then the French military attaché, and then the Mexican governors (the land was theirs, so they did not see why they should buy the fort), the manager, Alexander Rotchev, in December, 1841, sold the fort — and secretly much more — to John Sutter for $30,000. The last Russian ship departed on January 1, 1842.

Click to view:

Draft of Vallejo’s letter

Bancroft Library, Berkeley, California

(PDF file, 1.1 MB)

Transcription & Translation

(PDF file, small)

Amongst governor Mariano Vallejo's papers is a draft of a letter he may have sent to the Russian manager at Fort Ross stating the Mexican position; it is dated August 28, 1841, four months prior to the Russian departure. Vallejo wrote that no one in his department was authorized to purchase any part of Fort Ross for the Mexican government; and that, like his predecessor, he was denying the Russians their request for permission to sell the farms.

Not once was the settlement threatened by outside attack. The climate was mild yet invigorating, and the beauty of the surroundings imparted a sense of well-being recorded by many who were there. Manager Rotchev was to look back nostalgically at the time spent in this “enchanting land” as the “best years” of his life. — Fort Ross Conservancy

William Benitz – Sonoma County real estate:

We have summarised

his real estate transactions in

tables by county. Click: Sonoma County real estate transactions.

Measures used:

Distance: Legua or California league: 2.6 miles or 4.2 km.

Area: Sitio de Ganado Mayor or League: 4,340 acres or 1,756 hectareas

For more, see our page on Measures

(it opens on a new tab).

John A. Sutter’s declared purchase agreement with the Russians for Fort Ross, made on 12 December, 1841, was acceptable to the Mexican authorities because it did not include title to land. However, he had a prior contract, made in secret with the Russians in which they sold him the coastland 3 leagues deep (7¾ miles or 12½ km) between Point Reyes and Cape Mendocino (200 miles or 320 km): 1 milllon acres or 400,000 hectareas. Sutter kept this larger contract secret from the Mexicans against the day the U.S. took possession of California. At $30,000, Fort Ross alone appears overpriced; however, with the land included it was a bargain.

During 1842 and 1843, Sutter stripped Fort Ross of anything of value or that he could use at New Helvetia (a.k.a. Sutter’s Fort, today in Sacramento, CA); he took equipment, cannon, boats, and even dismantled houses. He also removed 2,000 head of Russian livestock (mostly cattle), herded to his Hock farm in the Sacramento valley (it was near present day Marysville).

Though his stewardship was not beneficial to its well-being, Sutter is credited with beginning the Ranch Era at Fort Ross.

In the fall of 1843 Sutter named William Benitz as his fourth manager at Fort Ross. Benitz held the post for almost two years. On 14 May, 1845, he signed a lease agreement (see below) with Sutter in which he could stay at the Ross establishment for as long as he wished, as Sutter’s agent, protecting Sutter’s interests. In exchange, Benitz would keep the proceeds from all crops except 1⁄3 of the fruit harvest, which would go to Sutter; livestock are not mentioned, nor exactly what comprised the Ross establishment. It is almost certain both parties believed it included the lands south of Fort Ross to the Russian River.

Benitz continued to live at Fort Ross after the land south of it had been granted to Manuel Torres in December, 1845 (see Smith & Torres below). We have not found supporting documents but we assume Benitz did, at least initially, provide Sutter his one-third share of the fruit crop from the Fort Ross orchards (north & east of the fort).

Manuel Torres (1826–1910), born in Lima, Peru, was 17 years old when he arrived in California in 1843 with his brother-in-law, Captain Stephen Smith (1782-1855).

Smith, an enterprising sea captain from Massachusetts, set up a saw-mill at Salmon Creek, just north of Bodega Bay. Because the area had been occupied by the Russians, Sutter claimed the land as his (see Sutter above) and sent John Bidwell to evict Smith. However, per the Mexican authorities, Sutter’s claim was unfounded, because neither they nor the Spanish had ever ceded ownership of the land to the Russians. Consequently, Smith, on 10 December, 1843, petitioned Governor Manuel Micheltorena for 8 leagues of land on the coast south of the Russian River. The governor granted it to Smith on 14 September, 1844, and it became his Rancho Bodega. However, Smith did have to pay Sutter for the buildings of the former Russian settlement at Bodega Bay.

Torres, following Smith’s example, petitioned Governor Micheltorena on 8 October, 1844, for the area known as Rancho de Muniz, described as 4 leagues of land 1 league wide along the coast north of Smith’s property (i.e., north of the Russian River) and south of the former Russian settlement (i.e. Fort Ross). It was granted to him by Governor Pio Pico on 4 December, 1845. Sutter was left with little more than the fort and its fruit orchards.

Muniz is a common Spanish family name and is probably a mispelling in Spanish of the Russian name Munin. Efim Munin was the Russian-American Company manager of the the Kostromitinov Ranch (the flatter lands along the coast north of the Russian River). He appears in the Ross census of 1821 and in 1838 he was met by a visiting Russian officer. (Please see “How the Muniz Rancho got its name” by Glenn Farris, Associate State Archeologist, Calif., June 6, 1996 (Fort Ross Conservancy Library: http://www.fortross.org/lib.html).

Rancho de Muniz

Transcripts

of the petition and grant

In original Spanish & translated into English

Book Toma de Razones

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office, Santa Rosa, CA

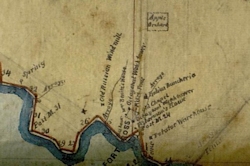

Diseño |

Expediente 488 Solicitud: “...concederme en propiedad un terreno que se halla baldío desde donde llegan

los limites del Señor Don Esteban Smith rumbo N. en estención de cuatro sitios de ganado mayor poco

mas ó menos, siendo sus linderos ál S. el Rancho del Señor Smith, al O. el mar, al poniente la Serranía

y al N. con el establecimiento que pertenecia á los Rusos, ...” ——♦—— Angeles, Diciembre 4 de 1845 ——♦—— “Pio Pico, Vocal decano de la Asamblea Departamental y

Gobernador provicional de las Californias. |

Proceedings 488 Petition: “...to grant me in ownership a tract of land

which is vacant, from the boundaries of Don Esteban Smith, towards the

North, of the extent of four square leagues, a little more or less; its

linderos [boundaries]

being on the South, the Rancho of Señor Smith; on the West, the Ocean; on the East, the mountains, and on the North

the Establishment belonging to the Russians; ...” ——♦—— “...Angeles December 4th 1845 ——♦—— “Pio Pico Senior Member of the Departmental Assembly and Provisional Governor of the Californias |

|

Haga click para

ver

todo el Expediente-488 (archivo PDF - 2,65 MB) |

Click to

view the entire Proceedings-488 (PDF file - 3.41 MB) |

We have not found a rental contract or lease agreement between Manuel Torres and William Benitz (or either of his partners: Ernest Rufus & Charles T. Meyer) by which Benitz & co. continued to use Rancho de Muniz for almost 6 years, from December, 1845, to May, 1851.

The absence today of such a contract does not mean it never existed. Surely, Stephen Smith, an older experienced businessman, would have encouraged his young brother-in-law, Torres, to obtain a formal rental agreement. If Torres and Benitz were on amicable terms, they may never have had need to register the contract. Notice how John Sutter waited 12 years, until 1857, to register the lease agreement he had made with Benitz in 1845; he did so because he was about to sue Benitz (see below).

... parcel of land, bounded and described as follows. Bounded on the Southward by the Russian River on the westward by the Northward by Fort Ross on the westward to the Pacific ocean and on the Eastward by the Coast range of mountains known and called by the name of the Rancho de Muny containing four leagues of land more or less, as granted unto the said party of the first part by deed dated at Monterey or Los Angeles, December fourth A.D. 1845 for the sum of Five Thousand dollars...

Book of Deeds "K", pages 850-851:

Sonoma Co. Recorder’s Office,

Santa Rosa, CA

On the 17th of May, 1851, William Benitz and Charles T. Meyer signed an agreement (promissory note) with Manuel Torres by which he would sell them Rancho de Muniz, giving them possession of the rancho upon receiving from them $5,000 dollars cash. The contract also stipulated that should they have made the exchange and the grant was not later confirmed to Torres by the United States he would refund them the money.

In the agreement, the description of the rancho changes just slightly with no effect upon its boundaries. Its southern boundary is defined explicitly as the Russian River, whereas in the grant it was defined awkwardly as the northern boundary of Steven Smith’s Rancho Bodega – which was the Russian River.

Click to view:

Promissory Note.

Book of Deeds “K”, pages 850-852

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office, Santa Rosa, CA

(PDF file, 1.5 MB)

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 2, 1848), by which Mexico ceded Alta California to the U.S., provided that Mexican land grants would be honored. As required by the Land Act of 1851, Manuel Torres filed a claim for Rancho de Muniz with the U.S. Public Lands Commission on February 17, 1852. It was confirmed to him by the Commission on December 27, 1853; and by the U.S. District Court on October 17, 1855. A later appeal against him was dismissed on May 7, 1857.

According to a letter by William Benitz to his brother Thad in Germany on March 8, 1855, he had recently bought out his partner (Charles T. Meyer), to whom he now owed $22,500, due on May 1, 1855. Presumably the debt was paid because Meyer signed a Quit Claim on August 11, 1855, relinquishing all claims to Rancho de Muniz for $1. In the Quit Claim, the definition of the rancho remains unchanged from that used by Torres when he sold it to them in 1851.

Click to view:

Quit Claim.

Book of Deeds “N”, page 321

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office, Santa Rosa, CA

(PDF file, 1.5 MB)

On July 9, 1855, John A. Sutter, Jr. (son), sold most, if not all, the property he held title to in Sacramento, and also the Russian Tract, i.e. Fort Ross and Rancho de Muniz. His father had given him title to the property years earlier, when he was a minor in Europe. Though Rancho de Muniz had been granted to Manuel Torres, Sutter’s claim to Fort Ross itself still had merit.

The announcement in the newspapers on August 1, 1855, must have alerted William Benitz that his claim to Fort Ross itself was, at best, weak; and, in all likelihood, he would now face legal challenges from the new owner, William S. Mesick.

... All that tract or parcel of land in the County of Sonoma and State of California bounded and described as follows on the South by the Russian River on the Westward by the Pacific Ocean & on the Eastward by the Cost range of Mountains & extending along the Coast Northerly about four leagues being the same Rancho formerly known as “Rancho de Muñez” containing four leagues of Land more or less granted to said Manuel Torres by Pio Pico Governor by deed dated at Monterey or Los Angeles December 4th 1845 & being the same tract of Land sold to said Bennetz & Charles Mayer by agreement dated May 17th 1857...

Book of Deeds "B", page 685:

Sonoma Co. Recorder’s Office,

Santa Rosa, CA

On April 13, 1857, William Benitz paid the $5,000 note he (now alone) owed Manuel Torres for Rancho de Muniz. The deed of sale made that day between Torres and Benitz changed the northern boundary of the rancho. For the first time, the Russian settlement (Fort Ross) is not mentioned in the rancho’s definition.

In the original grant, and all subsequent contracts before this one, the rancho was defined as 4 leagues bounded to the north by the Russian settlement, i.e. Fort Ross was its northern neighbor and therefore not part of Rancho de Muniz. However, in this deed of sale (Torres to Benitz), the rancho’s northern boundary was defined solely as about 4 leagues (10½ miles) north of the Russian River. This new definition placed the boundary 2-3 miles north of Fort Ross. That is, Rancho de Muniz now included Fort Ross.

The new definition must have been proposed by Benitz to give him title to Fort Ross, his family’s residence and his principal place of business. Its sale in 1855 to William Mesick (see above) must have shaken his trust in Sutter. Furthermore, Benitz must have believed the fort was more his than Sutter’s. Having received it from Sutter stripped of anything of possible value, Benitz had, in the twelve intervening years, repaired and improved almost all the Russian buildings and built several new ones inside and outside the stockade, transforming it into a viable agricultural enterprise, producing cereal crops (i.e. wheat, oats, barley), potatoes, fruit (from a new much larger orchard), livestock, and lumber.

Regardless, (1) per the original grant the fort was not Torres’ to sell, and (2) the new definition was in conflict with Benitz’s role as Sutter’s representative at the fort, per their lease agreement of 1845 (see above).

Click to view:

Indenture (Deed of Sale).

Book of Deeds “B”, pages 684-685

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office, Santa Rosa, CA

(PDF file, 0.8 MB)

In his first attempt at the preliminary survey, the surveyor made the tract too large at 22,742 acres (9,204 ha.). Per his notes, the grant’s four leagues called for 17,755 acres (7,185 ha.), so he removed 4,987 acres (2,018 ha.) by moving the eastern boundary west, making the tract narrower.

Click to view:

Field Notes of

Obsolete Survey

Completed May 22, 1857

(Courtesy of Glenn Farris)

(PDF file, 2.6 MB)

Some Observations: In both surveys, 1857 and 1859 (see below), the grant’s diseño (diagram, shown above) apparently superceded the grant’s written description:

... to call upon, ask and demand of Wm Benitz, of “Ross” on the former Russian Settlement in the county of Sonoma State aforesaid all property and sums of money, expressed in a certain lean bearing date the 14th day of May 1845. from the said John A. Sutter to the said Wm Benitz as belonging to said John A. Sutter and the use rents or profits thereof, as provided for and named and expressed in said lean and described as the “Establishment of Ross” ...

Powers of Attorney, Book “A”, page 23

Sonoma Co. Recorder’s Office,

Santa Rosa, CA

In early August, 1857, Sutter went into action to recover Fort Ross from Benitz. The Torres-to-Benitz sale in April and the US preliminary survey in May had both given Fort Ross to Benitz by placing it within Rancho de Muniz.

Sutter recorded their lease agreement of 1845 (see above) with the Sonoma County Recorder on August 1, 1857. Five days later, on August 6, 1857, he, his wife, and daughter registered a power of attorney naming his son Emil their representative in collecting all manner of rents and dues from Benitz. Apparently Emil failed to collect.

Sutter, in debt and in dire need of funds, disregarded the sale of the Russian Tract in 1855 (by his son John to William S. Mesick, see above) and sold his entire one-millon acre claim (the coastland between Point Reyes and Cape Mendocino) to Colonel William Muldrew in 1859.

... in consideration of the sum of Six Thousand Dollars ... have bargained sold and quit claimed ... the “Muniz Rancho”, commencing on the Coast of the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Russian River, and extending up the Coast North about Nine Miles, by an average depth of ⟨blank⟩ miles Eastward from the coast, containing according to the official survey thereof Four Leagues, or 17,760 acres more of less, bounded south by the Russian River and west by the Pacific Ocean, and being the same Rancho granted by the Mexican Government to Manuel Torres, ...

Book of Deeds “9”, page 431

Sonoma Co. Recorder’s Office,

Santa Rosa, CA

William Muldrew’s claim to the land that Sutter had bought from the Russians clouded several titles until an injunction was issued preventing him from selling any part of the Bodega Rancho. He tried surveying Rancho de Muniz, but Benitz dismantled Muldrew‘s house, removing it across the Russian River off the rancho.

Sutter, Muldrew, et al then filed suit against Benitz for Rancho de Muniz. The suit was settled on November 15, 1859. Benitz paid them off (he was the only land-holder to do so); in return, he obtained a quit claim from them that used the new definition for the rancho’s northern boundary, but set at approximately 9 miles from the Russian River. Though shorter than the 4 leagues (10½ miles) stipulated in the Torres-to-Benitz sale, the definition still included Fort Ross.

The $6,000 paid by Benitz to Sutter, Muldrew, et al has been characterized as extortion; however, it can also be viewed as payment for the purchase from Sutter of Fort Ross proper, its associated improvements and immediate land – which the Mexican authorities had recognised as belonging to Sutter, implied by Torres’ petition for Rancho de Muniz in which he excluded the Russian settlement (see Smith & Torres above).

Sutter paid $30,000 for Fort Ross; Benitz paid Sutter, Muldrew, et al $6,000. Including legal expenses, it apparently cost Benitz $8,000 - per his letter of January 18, 1863.

Click to view:

Indenture (Sale & Quit Claim).

Book of Deeds “9”, pages 431-432

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office, Santa Rosa, CA

(PDF file, 1.1 MB)

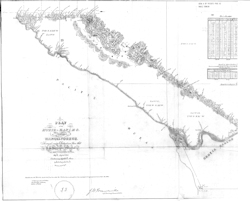

Plat of the “Muniz Rancho”

US Survey, 1859

Sonoma County Recorder‘s Office

Santa Rosa, CA

—‹♦›—

Fort Ross (excerpt)

Plat of the “Muniz Rancho”

US Survey, 1859

(Courtesy of Glenn Farris)

The U.S. surveyors established the boundaries of the Muniz rancho (October 4, 1859), including Fort Ross. It measured: 17,760¾ acres (7,1872⁄3 ha.), 162 acres more than 4 leagues. The survey was later confirmed and a patent was issued to Manuel Torres by the US Board of Land Commissioners (February 4, 1860). The sale of the rancho by Torres to Benitz was conditioned on obtaining that patent.

(Survey distances: Chains, links, & feet, see our page on Measures.)

|

Click to view: Patent & Final Survey (hand-written) Book of Patents “A” pages 69-82 (14) Sonoma County Recorder’s Office Santa Rosa, CA (PDF file, 6.4 MB) |

|

|

Click to view: Patent w/o Survey (typed, short) Abstract of Title List of Incumbrances pages 7-11 (4) prepared for the Call family (Courtesy of Lynn Rudy) (PDF file, 0.4 MB) |

Click to view: Field Notes of Final Survey Completed July 25, 1859 (typed, table format) pages 180-204 (25) (Courtesy of Glenn Farris) (PDF file, 5.7 MB) |

On 22 June, 1860, Benitz obtained confirmation from the District Judge for Sonoma County in Santa Rosa that the Rancho Muniz patent was genuine.

Click to view:

Patent

confirmation

Recorded in Book “A” of Patents, page 83

Sonoma County Recorder’s Office

Santa Rosa, California.

© Peter Benitz (Benitz Family)